The Battle of El Alamein

- Welcome to the PBS GAMETEAM's website, WE ARE RECRUITING. JOIN US and get a FREE VIP slot on our servers! -

- Our Thanks to Adaari, balz, hal, Bron,Yordy,Jonathan,Jozsef,BradJerney, wenz,Martin,Barry,chris, Ruben, Itsvan, Marko, Lan, Valter, Erik, joe, Matthew, Alois, Graig, Jason, caveman,Edwards, Jaimie, Ondre, Toby,Google, Phill, Gchrome,cramer,Rick,Jermey, lucas, kold, Roberto, Farq,Xiaton, Karlo, Rainman, Erik, Andrea and a very special thanks to our great premium members: Pon, Smekkes, Muttonchop,Krabbepote, Stoommeester, arjan, Xillax, Kapsta, Alexander,Duck, HausserBG, Bravecoward, Reint,Bas,Batuhan, Gunnar,Nuttycake,CJ Mini,tworooms,Jeffrey, Swag, Waverider, Sheepfarmer and Oberfield!for supporting the PBS GAMETEAM! -

- Do you like our servers or site? Support us on this page -

- Do you have a question? contact us -

- Join our Discord! -

- Check our latest news about our PBS games on this link -

- Would you like to donate for our servers? Please check this link -

- We are the best HLL, ARMA, BB, RS2, MW3 community out there! Sign up today! -

- Like us on Facebook! -

- Like us on Twitter! -

- We have many new wars! Check and signup here pls -

- Join our latest community event #here! -

- This topic has 1 reply, 1 voice, and was last updated 2 years, 1 month ago by

Lokisdad.

Lokisdad.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

23/05/2023 at 18:49 #103706

Fought near the western frontier of Egypt between 23 October and 4 November 1942, El Alamein was the climax and turning point of the North African campaign in the Second World War (1939-45). The Axis army of Italy and Germany suffered a decisive defeat by the British Eighth Army.

The context

Conflict in North Africa had been ignited in 1940 by Italy’s invasion of Egypt from its colony of Libya. This threatened Britain’s vital strategic assets, the Suez Canal and Persian oil fields. However, when the Italians were defeated, Germany intervened on behalf of its ally in the spring of 1941.

Under the bold leadership of General Rommel, the Axis enjoyed startling successes, recapturing Libya and threatening Egypt. Yet, by late 1941, when Rommel’s forces had overstretched their supply lines, they were forced to fall back in the face of a determined British offensive. The following year, a revived Axis effort saw Rommel defeat the British at Gazala and capture Tobruk.

In August 1942, General Claude Auchinleck had been relieved as Commander-in-Chief of Middle East Command and his successor, Lieutenant-General William Gott was killed on his way to replace him as commander of the Eighth Army. Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery was appointed and led the Eighth Army offensive.

The British victory at El Alamein was the beginning of the end of the Western Desert Campaign, eliminating the Axis threat to Egypt, the Suez Canal and the Middle Eastern and Persian oil fields. The battle revived the morale of the Allies, being the first big success against the Axis since Operation Crusader in late 1941. The end of the battle coincided with the Allied invasion of French North Africa in Operation Torch on 8 November, which opened a second front in North Africa.

Panzer Army Africa (Panzerarmee Afrika/Armata Corazzata Africa, Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel), composed of German and Italian tank and infantry units, had advanced into Egypt after its success at the Battle of Gazala (26 May – 21 June 1942). The Axis advance threatened British control of the Suez Canal, the Middle East and its oil resources. General Claude Auchinleck withdrew the Eighth Army to within 80 km (50 mi) of Alexandria where the Qattara Depression was 64 km (40 mi) south of El Alamein on the coast. The depression was impassable and meant that any attack had to be frontal; Axis attacks in the First Battle of El Alamein (1–27 July) had been defeated.

Eighth Army counter-attacks in July also failed, as the Axis forces dug in and regrouped. Auchinleck called off the attacks at the end of July to rebuild the army. In early August, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill and General Sir Alan Brooke, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), visited Cairo and replaced Auchinleck as Commander-in-chief Middle East Command with General Harold Alexander. Lieutenant-General William Gott was made commander of the Eighth Army but was killed when his transport aircraft was shot down by Luftwaffe fighters; Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery was flown from Britain to replace him.

Lacking reinforcements and depending on small, underdeveloped ports for supplies and aware of a huge Allied reinforcement operation for the Eighth Army, Rommel decided to attack first. The two armoured divisions of the Afrika Korps and the reconnaissance units of Panzerarmee Afrika led the attack but were repulsed at the Alam el Halfa ridge and Point 102 on 30 August 1942, during the Battle of Alam el Halfa; the Axis forces retired to their start lines. The short front line and secure flanks favoured the defensive and Rommel had time to develop the Axis fortifications, sowing minefields with c. 500,000 mines and miles of barbed wire.[15] Alexander and Montgomery intended to establish a superiority of force sufficient to achieve a breakthrough and exploit it to destroy Panzerarmee Afrika. Earlier in the Western Desert Campaign, neither side had been able to exploit a local victory sufficiently to defeat its opponent before it had withdrawn and transferred the problem of over-extended supply lines to the victor.

Until June 1942 Rommel had been receiving detailed information about the strength and movement of British forces from reports sent to Washington by Colonel Bonner Fellers, the U.S. military attaché in Cairo. The American code had been stolen following a covert operation by Italian military intelligence at the American Embassy in Rome the previous year. Despite British concerns, the Americans continued to use the code until the end of June. Suspicion that the code was compromised was confirmed when the 9th Australian Division captured the German 621st Signal Battalion in July 1942.

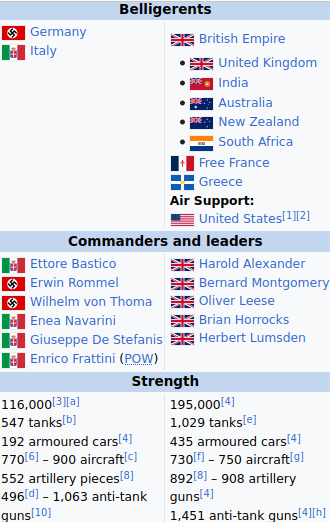

The British gained the intelligence advantage because Ultra and local sources exposed the Axis order of battle, its supply position and intentions. A reorganisation of military intelligence in Africa in July had also improved the integration of information received from all sources and the speed of its dissemination.[17] With rare exceptions, intelligence identified the supply ships destined for North Africa, their location or routing and in most cases their cargoes, allowing them to be attacked.[18] By 25 October, Panzerarmee Afrika was down to three days’ supply of fuel, only two days’ of which were east of Tobruk. Harry Hinsley, the official historian of British intelligence, wrote in 1981 that “The Panzer Army…Â did not possess the operational freedom of movement that was absolutely essential in consideration of the fact that the British offensive can be expected to start any day”.[19] Submarine and air transport somewhat eased the shortage of ammunition and by late October, there was sixteen days’ supply at the front.[19] After six more weeks, the Eighth Army was ready; 195,000 men and 1,029 tanks began the offensive against the 116,000 men and 547 tanks of the Panzerarmee.

British plan

Operation Lightfoot

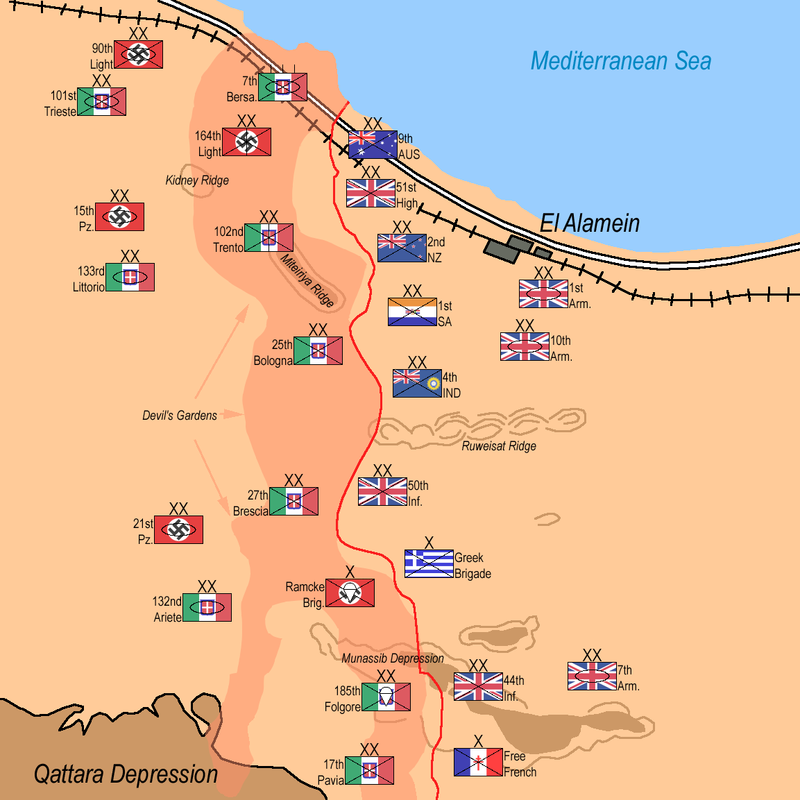

Montgomery’s plan was for a main attack to the north of the line and a secondary attack to the south, involving XXX Corps (Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese) and XIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks), while X Corps (Lieutenant-General Herbert Lumsden) was to exploit the success.[20] With Operation Lightfoot, Montgomery intended to cut two corridors through the Axis minefields in the north. One corridor was to run south-west through the 2nd New Zealand Division sector towards the centre of Miteirya Ridge, while the second was to run west, passing 2 mi (3.2 km) north of the west end of the Miteirya Ridge across the 9th Australian and 51st (Highland) Division sectors.[21] Tanks would then pass through and defeat the German armour. Diversions at Ruweisat Ridge in the centre and also the south of the line would keep the rest of the Axis forces from moving northwards. Montgomery expected a 12-day battle in three stages: the break-in, the dogfight and the final breaking of the enemy.

For the first night of the offensive, Montgomery planned for four infantry divisions of XXX Corps to advance on a 16 mi (26 km) front to the Oxalic Line, over-running the forward Axis defences. Engineers would clear and mark the two lanes through the minefields, through which the armoured divisions from X Corps would pass to gain the Pierson Line. They would rally and consolidate their position just west of the infantry positions, blocking an Axis tank counter-attack. The British tanks would then advance to Skinflint, astride the north–south Rahman Track deep in the Axis defensive system, to challenge the Axis armour.[21] The infantry battle would continue as the Eighth Army infantry “crumbled” the deep Axis defensive fortifications (three successive lines of fortification had been constructed) and destroy any tanks that attacked them.

Operation Bertram

Main article: Operation Bertram

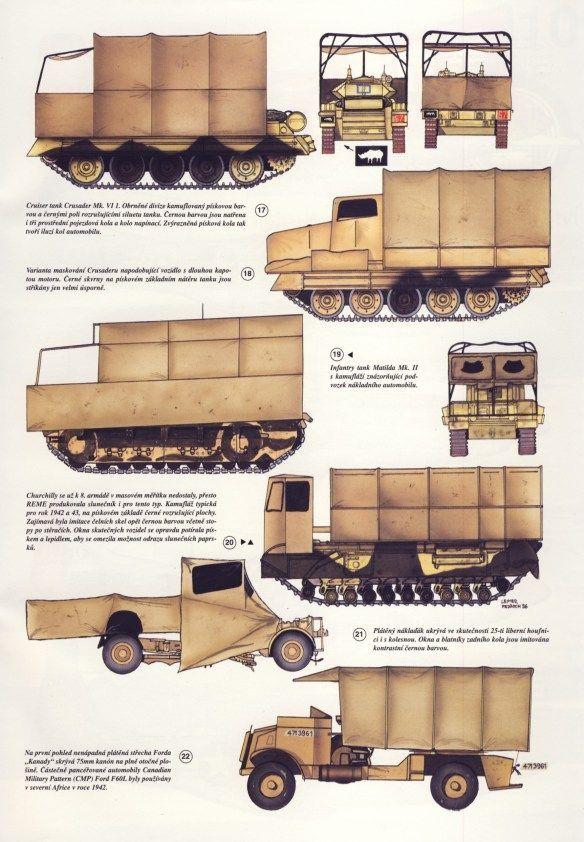

Before the battle the Commonwealth forces practised deceptions, in Operation Bertram, to confuse the Axis command as to where and when the battle was to occur. In September, they dumped waste materials (discarded packing cases, etc.) under camouflage nets in the northern sector, making them appear to be ammunition or ration dumps. The Axis naturally noticed these but as no offensive action immediately followed and the “dumps” did not change in appearance, they were subsequently ignored. This allowed the Eighth Army to build up supplies in the forward area unnoticed by the Axis, by replacing the rubbish with ammunition, petrol and rations at night. A dummy pipeline was built, hopefully leading the Axis to believe the attack would occur much later than it did and much further south. Dummy tanks consisting of plywood frames placed over jeeps were built and deployed in the south. In a reverse feint, the tanks destined for battle in the north were disguised as supply trucks by placing removable plywood superstructures over them.

Operation Braganza

Main article: Operation Braganza

As a preliminary, the 131st (Queen’s) Infantry Brigade of the 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division, supported by tanks from the 4th Armoured Brigade, launched Operation Braganza attacking the paratroopers of the 185th Paratroopers Division “Folgore” on the night of 29/30 September in an attempt to capture the Deir el Munassib area. The Italian paratroopers repelled the attack, killing or capturing over 300 of the attackers.[26] It was wrongly assumed that Fallschirmjäger (German paratroopers) had manned the defences and been responsible for the British reverse. The Afrika Korps war diary notes that the Italian paratrooper unit “bore the brunt of the attack. It fought well and inflicted heavy losses on the enemy.

Axis plan

Deployment of forces on the eve of battle

With the failure of their offensive at the Battle of Alam el Halfa, the Axis forces went onto the defensive but losses had not been excessive. The Axis supply line from Tripoli was extremely long and captured British supplies and equipment had been exhausted, but Rommel decided to advance into Egypt.

The Eighth Army was being supplied with men and materials from the United Kingdom, India, Australia and New Zealand, as well as with trucks and the new Sherman tanks from the United States. Rommel continued to request equipment, supplies and fuel but the priority of the German war effort was the Eastern Front and very limited supplies reached North Africa. Rommel was ill and in early September, arrangements were made for him to return to Germany on sick leave and for General der Panzertruppe Georg Stumme to transfer from the Russian front to take his place. Before he left for Germany on 23 September, Rommel organised the defence and wrote a long appreciation of the situation to Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW armed forces high command), once again setting out the essential needs of the Panzer Army.

‘The defeat of the enemy in the Battle of El Alamein, the pursuit of his beaten army and the final capture of Tripoli… has all been accomplished in three months. This is probably without parallel in history’.

Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery, 23 January 1943

Georg Stumme in 1940

Rommel knew that the British and Commonwealth forces would soon be strong enough to attack. His only hope now relied on the German forces fighting in the Battle of Stalingrad quickly to defeat the Red Army, then move south through the Trans-Caucasus and threaten Iran (Persia) and the Middle East. If successful, large numbers of British and Commonwealth forces would have to be sent from the Egyptian front to reinforce the Ninth Army in Iran, leading to the postponement of any offensive against his army. Rommel hoped to convince OKW to reinforce his forces for the eventual link-up between Panzerarmee Afrika and the German armies fighting in southern Russia, enabling them finally to defeat the British and Commonwealth armies in North Africa and the Middle East.In the meantime, the Panzerarmee dug in and waited for the attack by the Eighth Army or the defeat of the Red Army at Stalingrad. Rommel added depth to his defences by creating at least two belts of mines about 3.1 mi (5 km) apart, connected at intervals to create boxes (Devil’s gardens) which would restrict enemy penetration and deprive British armour of room for manoeuvre. The front face of each box was lightly held by battle outposts and the rest of the box was unoccupied but sowed with mines and explosive traps and covered by enfilading fire.[31] The main defensive positions were built to a depth of at least 2 km (1.2 mi) behind the second mine belt. The Axis laid around half a million mines, mostly Teller anti-tank mines with some smaller anti-personnel types (such as the S-mine). (Many of these mines were British and had been captured at Tobruk). To lure enemy vehicles into the minefields, the Italians dragged an axle and tyres through the fields using a long rope to create what appeared to be well-used tracks.

Marshal Ettore Bastico

Rommel did not want the British armour to break out into the open because he had neither the strength of numbers nor fuel to match them in a battle of manoeuvre. The battle had to be fought in the fortified zones; a breakthrough had to be defeated quickly. Rommel stiffened his forward lines by alternating German and Italian infantry formations. Because the British deception confused the Axis as to the point of attack, Rommel departed from his usual practice of holding his armoured strength in a concentrated reserve and split it into a northern group (15th Panzer Division and 133rd Armoured Division “Littorio”) and a southern group (21st Panzer Division and 132nd Armoured Division “Ariete”), each organised into battle groups to be able to make a quick armoured intervention wherever the blow fell and prevent narrow breakthroughs from being enlarged. A significant proportion of his armoured reserve was dispersed and held unusually far forward. The 15th Panzer Division had 125 operational tanks.Rommel held the 90th Light Division further back and kept the 101st Motorised Division “Trieste” in reserve near the coast.[34] Rommel hoped to move his troops faster than the Allies, to concentrate his defences at the most important point (Schwerpunkt) but lack of fuel meant that once the Panzerarmee had concentrated, it would not be able to move again because of lack of fuel. The British were well aware that Rommel would be unable to mount a defence based on his usual manoeuvre tactics but no clear picture emerged of how he would fight the battle and British plans seriously underestimated the Axis defences and the fighting power of the Panzerarmee.

Don’t fight a battle if you don’t gain anything by winning.

Erwin Rommel

-

26/05/2023 at 10:02 #103866

‘the Qattara Depression .. was impassable’.

Tell that to the SAS! This was the time that the SAS had just been formed (Sept ’42). In conjunction with the Long Range Desert Force they operated behind enemy lines, using the impassable Qattara depression, to attack Axis airfields and ports. There’s an excellent TV series about their creation called SAS Rogue Heroes; if you haven’t seen it, I highly recommend it. You could be forgiven for believing that it was a creation of an imaginative TV writer but 99% of it is factual.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.